Red Skies, Red Garters

If Star Trek’s “Spectre of the Gun” is known for anything it’s for its abstract town setting and blood-red sky. But like so many things Trek though it’s been discussed for 50 years there are a number of misapprehensions and myths around the making of this episode, from why writer Gene Coon employed a pseudonym to what likely inspired that unreal setting.

So, cowpokes, saddle up and follow us down this dusty, seldom trod trail, because we’re riding out to Limbo County to find see if there’s historical gold in them thar hills at the outskirts of Stage 10.

See You Space Cowboy…

Although Star Trek was in ways a Western in space—Gene Roddenberry even called it a “Wagon Train to the stars” in its earliest pitch—this episode was the only one to overtly evoke such “oaters”. Sure, “Mudd’s Women” played on the idea of “wiving” and frontier/mail-order brides, but there was nary a six-gun, saloon, or horse—let alone a cowboy hat—to be seen.

The first segment shot for the season, “Spectre” was the sixth aired, making its NBC debut on October 25, 1968: just a day shy of the 87th anniversary of the (in)famous so-called “gunfight at the O.K. corral” on which it centers.

Writing

Moonlighting

The credits for “Spectre of the Gun” list a writer named “Lee Cronin.” This was a pen name used by Gene L. Coon, Star Trek’s former producer, while he was under exclusive contract with Universal during the 1968-69 season, and working on It Takes A Thief. The Cronin “teleplay by” Trek scripts were "Spectre of the Gun" and "Spock's Brain", with “story by” credit on "Wink of an Eye" and "Let That Be Your Last Battlefield" (which means he sold the story outlines but did not end up writing the scripts, possibly due to his commitments at Universal).

The Lee Cronin pseudonym allowed Coon to fulfill his obligation to write more scripts for Star Trek, which he agreed to do when he stepped down as the show’s producer in 1967, while also maintaining the fiction with Universal that he wasn’t moonlighting on non-Universal shows.

The people at Star Trek played along, of course. After viewing a cut of the episode, Gene Roddenberry sent Gene L. Coon a letter, writing, “I saw a final cut on a rather bizarre type of Western, written by a mutual friend of ours, and it looked very good indeed!”[1]

However, Roddenberry wasn’t writing to Coon from the Star Trek offices. He had turned over his digs there to third-season producer Fred Freiberger. And while he maintained a small office elsewhere on the Paramount lot, he was often working at an office at the National General Corporation. Why? To write a never-to-be-made feature film script based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan—but that’s a topic for another time.[2]

Where Roddenberry was roosting. Source: logos.fandom.com (link)

And speaking of absentee landlord Roddenberry…

As this was the first episode produced for the third season and the first for newly hired Freiberger, Roddenberry wrote rather extensive notes concerning not merely this script’s particulars but broader guidance on how Star Trek works and when it doesn’t. It’s “fascinating” reading which we’ll address at a future date. One thing it makes clear is that the — contrary to some fan rumors — NBC didn’t push for Spock to be more prominent in the episode. It was Roddenberry who was critical of Kirk being portrayed as having so much expertise on the Old West and that Spock was underutilized. He explained that previous episodes had established Spock as an expert on history and that much of this information should be shifted to him. And thus it was.[3]

Outline Draft or Copy?

If you consulted the work of Marc Cushman, you’d be led to believe that Gene L. Coon wrote a 2nd draft outline for “The Last Gunfight” dated 4/19/68. His These Are The Voyages states “His [Coon’s] revised story outline, written for free and incorporating many of Justman and Roddenberry’s ideas, was dated April 19.”[4] This is wrong—Coon only delivered a single outline for the episode (dated 3/18/68 and received by the Star Trek offices 3/22/68).[5]

Coon’s Story Outline was retyped for mimeograph. The content is the same.

How did this error arise? Well, there is an outline dated 4/19/68 for this episode in the production files held by UCLA—but a close examination reveals that its text is identical to the draft dated 3/18/68. (In light of that, Cushman’s contention that the 4/19/68 version incorporated suggestions from Roddenberry and Justman memos is nonsense.) But why does the same story outline have two wildly different dates?

If one consults the many Star Trek story outlines at UCLA, there’s a clear pattern. The studio always re-typed outlines (and scripts) that came in before sending them to NBC for story approval. Usually, the turnaround time was a few days, but here it was longer.

Why retype? Photocopiers were expensive, so mimeograph was employed for duplication. It required a special “master” be made for each page, which necessitated all submitted scripts be retyped. “Stone knives and bear skins,” indeed.

If you finished high school after the 1980s the mimeo will probably be as foreign to you as a word processor would be to the secretaries on Star Trek in 1968.

Mimeo was also the point at which documents were standardized. While not important for story outlines, TV scripts conform to a particular format and type size, and more than one writer turned in a script seemingly of the correct number of pages only to find they ran long or short after being retyped for mimeo…David Gerrold, for one.[6]

Supporting this, a Monday, April 22nd cover letter from Fred Freiberger to NBC’s Stanley Robertson indicates it's the first time “The Last Gunfight” outline had been sent to the network. The only reason for such a delay would be waiting for it to be retyped for Mimeo so copies could be distributed.[7] And, indeed, the retyped treatment was dated the previous business day: Friday the 19th.

What’s In a [Script] Name?

When the initial story for what eventually became “Spectre of the Gun” was assigned to Coon/Cronin on March 6, 1968, it was called “Execution, 1872.”[8] That was probably a working title—after all, the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral took place on October 26, 1881—and by the time Coon delivered his first draft story outline on March 22, 1968, he had changed the title to “The Last Gunfight.”

This title stuck with the episode throughout filming and into early post-production. It even ended up as the title of James Blish’s adaptation of the episode, published in the book Star Trek 3 in April of 1969.

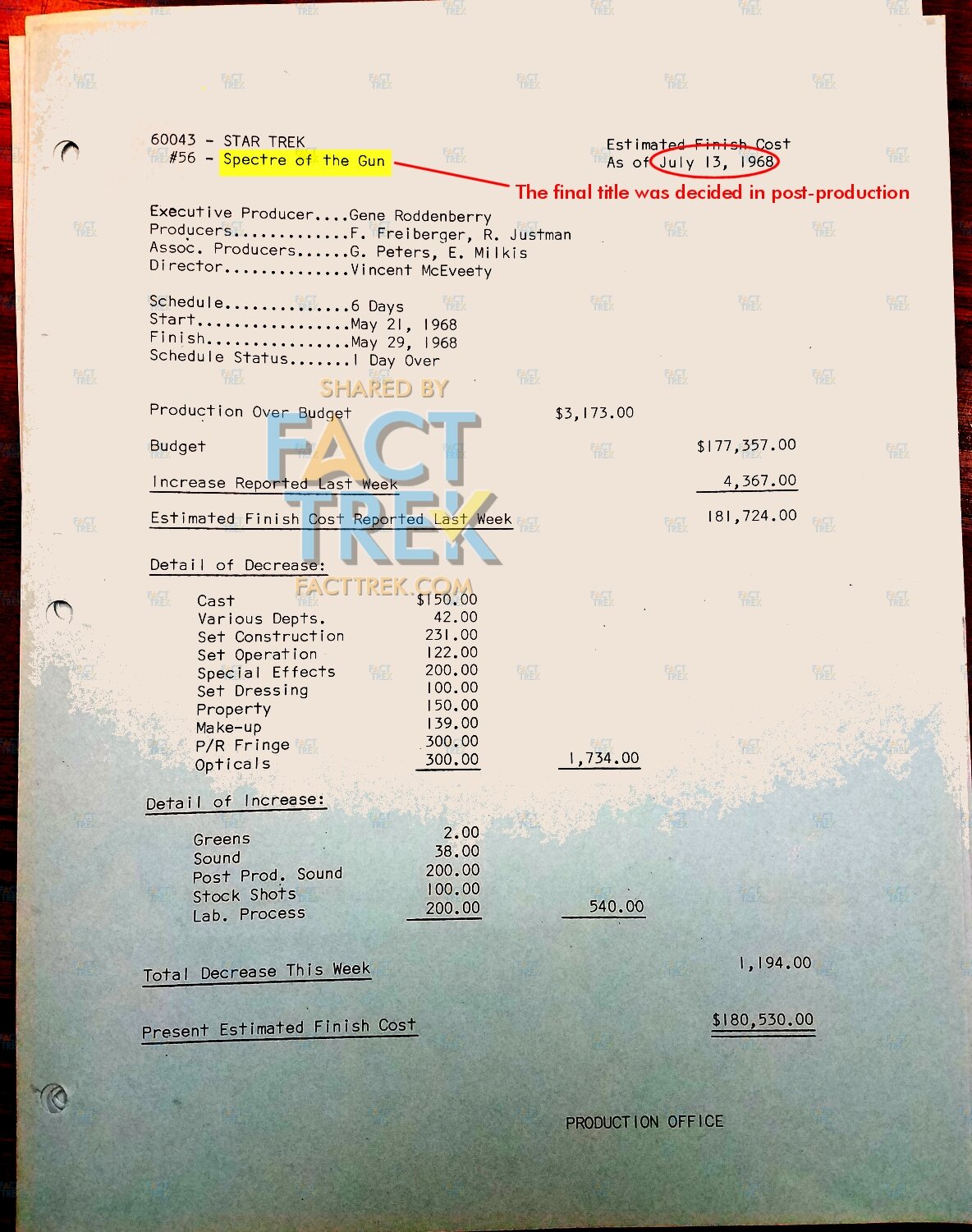

On June 27, 1968, however, co-producer Bob Justman sent a formal memo to all the key people involved with Star Trek and indicated there would be a title change to “The Spectre Of The Melkot.”[9] That name didn’t stick, and weekly budget paperwork for the episode still carries the title “The Last Gunfight” until the week of July 13, 1968—when the episode received its fourth and final title in “Spectre of the Gun.”[10]

The episode title as aired seems a mash-up of "The Spectre of the Melkot" and—perhaps—plays on the title of John Sturges’ follow-up to his 1957 O.K. Corral film, 1967’s Hour of the Gun,[11] which was about the aftermath of the famous gunfight and released in the US only 8½ months before “Spectre” got its final title.

As we write this Hour of the Gun‘s depiction of the shootout can be viewed online (see below).

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral is depicted in this film's opening scene.

Casting

Bones McEarp

DeForest Kelley was no stranger to Westerns in general and the story of the Earps and Clantons in particular. In the November 6, 1955 episode of You Are There he played the role of Ike Clanton. (You Are There portrayed historical events as if they were happening now, with interviewers quizzing the participants.)

Two years later he switched sides to portray Morgan Earp in the John Sturges feature Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), which starred Burt Lancaster as Wyatt Earp and Kirk Douglas as Doc Holliday. And for “Spectre” he switched sides again as Bones McCoy was forced to assume the role of Clanton ally Tom McLaury.

Speaking of that name, Coon has spelled it McClawrey, but—weirdly—when de Forest Research pointed out the mistake, they provided an erroneous spelling: McLowery for McLaury:

Frank and Tom McClowery, Billy Claiborne, Billy Clanton. – McLowery is the correct spelling of this name. Suggest regularize here and throughout script. See note ahead for 13/25 re Ike Clanton.)[12]

DeForest Kelly (right) as Morgan Earp in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957)

There’s a further claim regarding Kelley, one that we’re not entirely inclined to believe as the pieces making the claim do not cite any sources. The first…

Believe it or not, DeForest Kelley almost had one more shot—he did four—at appearing in a Tombstone—related movie or TV episode.He’d played Morgan Earp in 1957’s Gunfight at the OK Corral—and lived, unlike the real Morgan. The sequel, Hour of the Gun, came out in 1967 and producers demanded that different actors play the main roles. There were two exceptions: John Hudson, who played Virgil Earp and DeForest Kelley. Kelley wanted to take the part—he really liked doing Westerns—but shooting for Star Trek prevented his taking the job.[13]

The second…

As for the rest of the cast, Sturges (1911-1992) initially chose to reuse the actors who played Earp’s brothers from the previous movie, but as it turned out, none of them were available (including Star Trek’s DeForest “Dr. McCoy” Kelley)[14]

Take those with a salt lick of salt, pardner.

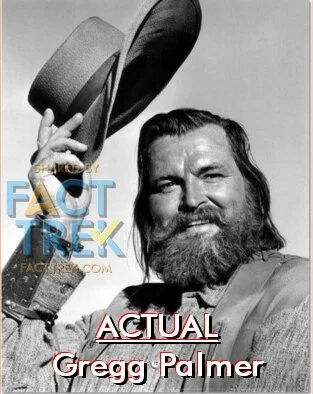

The Tale of the Axed Ox

When we initially wrote this, both the Star Trek wiki Memory Alpha and IMDb listed actor Gregg Palmer as the (uncredited) “Rancher”. Memory Alpha has since corrected this, but since their articles are often copied, we’ll address a since-removed error that went so far as to identify him as the man Morgan guns down outside the Saloon.[15] But there's just one teensy problem: the man in question isn't Gregg Palmer. Looks nothing like him. In fact, Palmer isn’t in the episode at all. He'd be impossible to miss given his height (upwards of 6’3“) and heavy build. So what gives?[16][17]

First, the man who gets a belly full of lead is probably a stuntman (possibly Paul Baxley). So why did anyone assume Gregg Palmer was in the episode? Well, he does appear on a May 22 revised Cast Sheet as a “Rancher”. So where is he?

Guess what? An OMITTED scene!

(To avoid confusion, when scenes are removed from a script their numbers remain in the script but accompanied with the tag “OMITTED”.)

Palmer was cast to play an unnamed “huge ox of a man”, an “incensed rancher” who accuses Spock aka “Frank McLowrey” [sic] of “cattle rustling.” Spock tries some Vulcan mind trick on him—a la "The Omega Glory"—but here it fails completely and the ox of a Rancher throws him around and roughs him up before Spock finally applies ye old FSNP (Famous Spock Neck Pinch) and ends the confrontation.

But although Palmer was cast as the Rancher, his scenes were never shot. He doesn’t appear on any of the episode's call sheets or the daily production reports. In fact, the report for Day 4 indicates that the scenes featuring the Rancher—49, 50, 51 & 53—were amongst those OMITTED (not filmed). This is buttressed by a script page revision dated 5/28/1968—the day those scenes were to be shot—which reads "49 thru 53 OMITTED".

Perhaps it’s just as well, as this stuff is pure corn... er, Coon.

Fact Trekkers

Star Trek’s scripts were routinely reviewed and fact checked by de Forest Research, which provided even more extensive notes than usual for the script of “The Last Gunfight”,[18] repeatedly cautioning that as the incident was such a well-known historical event many members of the audience would spot any gaffes in the telling.

Such notes included:

You’ve got until five tonight to get your horse stealing scurvy crew out of town – (or he’ll make them walk the plank, perhaps?) “Scurvy crew” is a term drawn from 18th century naval slang and hardly seems in character for Wyatt Earp. Suggest delete. We find no record of the five o’clock time limit.

Neither of these suggestions was heeded, so Wyatt talks like a pirate and the gunfight takes place just after five o’clock (though in reality, it was closer to three).

Also…

The slon-farr – Mr. Cronin cannot seem to keep his own Vulcan terminology straight. He uses “slon-farr” in Spock’s Brain with an entirely different meaning. Star Trek has a firmly established term for this particular discipline: Vulcan mind-melding. Suggest change to “Vulcan mind melding” to conform with precidents.[sic]

Chek[h]ov’s Gun[s]

These de Forest Research notes included numerous details on many of the firearms used in the story. One note in particular was that…

Chekov (Billy Claiborne) should have two guns. Claiborne affected two guns always.

…and in the episode, he does. Note that his crewmates each carry one.

De Forest Research was not always correct, however. They also recommended that Wyatt carry a “Buntline Special”, popularized in Stuart N. Lake’s dubious and fanciful 1931 biography, Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal.[19] The show heeded this advice and this is the weapon Wyatt has at the top of the scene in the Marshall’s office though not at the shootout. But a little digging shows that there’s little to indicate what weapons were actually used that day.[20]

Lake even armed his hero [Wyatt] with a Buntline Special, a Colt Peacemaker with an extra long barrel, an embellishment for which there is no evidence.[21]

They further advised that…

Holliday usually carried a nickel-plated six gun. He did carry a short Wells-Fargo shotgun in his right hand at the OK Corral. He slipped his right arm out of his coat sleeve and draped the coat over his shoulder, cape like, to conceal the weapon. Implications that the shotgun was his usual weapon is erroneous and might bring repercussions.

In the episode, Doc drapes his coat as suggested, but neither the recommended nickel-plated six gun nor the admonition regarding shotguns were heeded; Doc pulls the shotgun on Bones in the barbershop scene.

Production

Horseplay Hooey

Like much about Star Trek, there are several misconceptions about "Spectre of the Gun" worth addressing. The first involves a sequence that did not make it to air: a bit of literal horseplay involving Captain Kirk. (See images of these pages below and what the scene involved.)

It seems Coon was trying to make this business with Kirk and a horse another funny “flivver” moment a la “A Piece of the Action” (the business of Kirk trying to drive a 1931 Cadillac Roadster that Spock refers to as a "flivver"). Such broad humor largely vanished after Coon’s Star Trek tenure ended.

According to Marc Cushman’s These Are Voyages, this business with the Rider, Kirk and a couple of horses was filmed for “Spectre of the Gun,” but cut during editing. The documentary evidence says otherwise. (See his questionable account in the attached capture.)[22]

Neigh.

The issue? The very scenes Cushman says were filmed (55–57) were dropped from the shooting script prior to the day he claims they were filmed, as called out in the revised final draft script pages dated 5/27/68.

Coon’s horseplay scenes rode into the sunset without being filmed

This whole business may have been cut at the behest of Roddenberry, who questioned the validity of the scene in a memo to Fred Freiberger concerning the May 9th Final Draft, opining that it made Kirk look “simple-minded”.[23]

Roddenberry’s low opinion of Coon’s scripted horseplay.

A further strike against his account: according to the daily production reports the horses rented for this episode were only on set for the first three days of filming (May 21-23). Those production reports line up with the script and what’s seen in the episode, where horses appear outside the Saloon in Scenes 29 and 53A, shot on day 1, and a horse appears throughout the aired OK Corral sequence, in the scenes shot on days 2 and 3. Cushman claims this fancy horse stunt was filmed on “Day 6”, but the paperwork indicates precisely zero horses were on set that day.

Then there’s the claim that Dick Dial did the OMITTED stunt. While Dial did do stunt work on Star Trek (and later on Star Trek: The Next Generation), the production reports show he wasn’t in “Spectre of the Gun” at all.

No horses. No Dial. No Dice.

Lastly, there’s Richard Anthony—listed on the May 22 revised Cast Sheet as the “Rider,” a single-line role that had been cut by the May 17 revisions. That this name remained on the Cast Sheet was likely a mistake due to Scene 54 being truncated, not OMITTED.

FACT TREK NOTE: IMDb mistakenly credits this dropped part as having been cast with Egyptian-born singer/actor Ibrahim Richard Btesh, aka “Richard Anthony”, but the man cast for the role was actually the kid brother of Desilu casting director Joseph D’Agosta: Richard Ray D’Agosta, who chose the screen name of Richard Anthony. The junior D'Agosta was a stand-in of Desi Arnaz Jr. and stuntman, and the scene required a stunt.[24]

The clincher: No production report lists the OMITTED scenes 55-57 having been shot. Sure, occasionally scene numbers were left off paperwork due to human error, but in light of all the evidence above, we’re confident these horseplay scenes were never filmed. The story that they were—and that an actor whose role was dropped and a stuntman who didn’t work on that episode “spent a few hours with McEveety filming the complex routine”—is pure fabrication and horse manure.*

Exit Earp

In the final episode, actor Rex Holman plays Morgan Earp, identified by Kirk as “the man who kills on sight.” However, Holman was originally cast in the smaller role of Virgil Earp, and when he reported to work on May 22, 1968, at 8:30 a.m., he did not yet know he would be upgraded to the better-paying role of Morgan.[25]

A different actor—identified by the daily production reports as both “Gregory Reece” and “Gregory Reese”—had been cast as Morgan and appears to have already filmed some scenes the day before (Morgan’s non-dialogue action in scenes 28–30, when he guns down a bar patron in front of Kirk and company). Reese returned to work on May 22, reporting for make-up at 7:00 a.m. and appearing on set at 8:00 a.m. But by 11:00 am—at the request of director Vincent McEveety—Reese was fired by the show’s producers. It’s unclear if he filmed any additional scenes that morning. According to the notes from the May 22, 1968 daily production report:

Director Vincent McEveety asked the producers to replace an actor because of many delays and inability to comprehend scenes. The producers concurred realizing that the delays would seriously affect the shooting schedule. It was learned from casting director Joe D’Agosta that the actor had personal problems which also affected his work. The producers decided to drop the actor from the production. The actor is to be paid the full amount of his contract. Due to re-casting and re-takes, the estimated production time lost was approximately three (3) hours.[26][26a]

Casting director Joe D’Agosta told us a story about once having to down to the Trek set to fire a problematic actor. Upon seeing the production report above he indicated this was likely the incident in question.[26b]

Cushman reports that re-shooting the scenes with Morgan Earp was “first up” on the second day, but this is counter to the production reports cited above, which make it clear that Reese was on set for several hours that day before being dismissed. Cushman also misreports the name of the fired actor, writing at one point that “a third actor to be identified here only by his first name, Reece” was cast in the role of Morgan Earp.[27] Reece—or, more likely, Reese—was in fact the actor’s last name.

IMDb lists no credits for “Gregory Reece” but does list two credits for an actor named “Gregory Reese”—a guest role as “Lyle Stukey” on an episode of N.Y.P.D. (“Fast Gun,” originally aired September 26, 1967) and a small part as “Foglio” in Shaft’s Big Score (1972).[28]

Additional research turned up several references to a New York theater actor named “Gregory Reese,” who was active during the same period. While we can’t be absolutely certain this is the same actor who appeared in N.Y.P.D. and Shaft’s Big Score, the timing and New York location makes us suspect they’re one and the same. In any case, the Mr. Reese who appeared on the New York stage first showed up in “God Wants What Men Want” in April of 1966.[29] The following year, he was part of The Young People’s Repertory Theatre, where he appeared in “When Did You Last See My Mother?” and “Antigone,” both staged in January of 1967.[30] And, for a separate theatre company during the same month, he appeared in the play “Fortune and Men’s Eyes.”[31] We could find no professional stage credits after that.

Rex Holman, who assumed the role of Morgan Earp when Reese was fired, had a more prolific acting career after Star Trek, frequently guest starring in television Westerns including The High Chaparral, Gunsmoke, The Big Valley, and The Virginian. His final screen credit to date—as of this writing, he’s still kicking at age 91—was the role of J’onn in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989).

Now Entering Limbo County

The production design of “Spectre of the Gun” is known for featuring an impressionistic, incomplete Western setting.

The Star Trek credits lettering makes an unexpected cameo.

Reality was not quite so abstract… [32]

But Gene Coon’s original March 18th story outline indicates "a hot blue desert sky, a hot yellow desert sun, with the street of a Western town stretching before them..." No indication of anything odd or surreal.

The outline’s setting is so literally a Western town that the landing party find themselves in full cowboy clothes! One imagines Coon expected them to shoot on a studio backlot. But by the May 9, 1968 Final Draft script of "The Last Gunfight", we get this:

So, by this point, at least, the script called for a less real Western town. And in a lengthy memo to Producer Fred Freiberger May 15, 1968, Roddenberry expresses mild concern over “some kind of non-realistic sets” he says Freiberger and Co-Producer Justman plan.[33]

The Great Bird of the Galaxy had worries…

…but producer Fred Frieberger backed Justman’s idea.[33a]

Every time Star Trek went on location, the episode went over budget. In the 3rd season the show only went outside the soundstages twice: first for “The Paradise Syndrome” and finally for some backlot shooting for “All Our Yesterdays.” Because of the illusory nature of the affair, “Spectre” clearly lent itself to a more artificial presentation than “The Paradise Syndrome”, and that may have led to the decision to do their one major location shoot for the season for “Paradise”.

Star Trek Art Director Matt Jefferies’ soundstage-bound Tombstone sets are incomplete structures with the occasional object suspended in the air and a blood-red sky…fragmentary and unreal. It’s more a suggestion of a place than an actual location. It’s conventional wisdom that this was some innovative, brilliant solution to the third season budget issues (Paramount cut the budget even as NBC was paying more for the show). But is that truly where it came from? Or was there an antecedent Jefferies was riffing on?.

Some ‘60s SciFi TV fans may remember that two years earlier, over on CBS, a second season episode of Lost in Space titled “West of Mars” featured a strikingly similar nonrealistic Western town set. Both “Spectre” and “Mars” were the only overtly “Western” episodes of their respective series and yet arrived at the exact same design solution. Convergent evolution? Coincidence?

Before you say it, yes, Lost In Space did “limbo” sets to death (so did Batman in its 3rd and final season), but a typical limbo set is a void with set pieces and dressing where we assume there are either no walls or they are lost in the distance or darkness.

A typical Lost In Space limbo set.

Star Trek itself pulled the limbo trick in “The Empath”, where—funnily enough—the Jupiter II freezing tubes from Lost In Space make an appearance (the show had been canceled).

Star Trek’s “The Empath.” Black limbo with scattered set bits around.

Such limbo sets are not abstracted environs where structures are suggested by facades, floating windows and free-standing doorways that characters consistently walk through as if the wholly absent walls were present.

Why bother with the door, Chekov?

But “Don’t Panic,” Jefferies surely wasn’t referencing “West of Mars” on Lost In Space. In fact, both episodes appear to have a common inspiration. Each looks to be aping Paramount’s musical comedy Western Red Garters (1954),[34] which featured abstracted Western sets with literal facades, freestanding doorways, floating windows, and an almost complete absence of walls all set against bold background colors.

Look a bit familiar?

As Fernando Usón Forniés wrote on his Cinéphile caprice blog [35]:

The set, of unheard of radicalness for a "conventional" film, since it limits itself to sketching the frame and the doors of the buildings […][W]hat is truly surprising about this film […] lies in its manifest unreality, in the continuous reminder to the viewer that he is before a representation.

This as neatly describes “Spectre of the Gun” as it does the “Limbo County, California” setting of Red Garters. The sets of the former are so close to the latter—particularly the omnipresent blood red of illusory Tombstone’s sky to the identical background color in the film’s Red Dog saloon—that one can imagine Kirk and the boys stepping in to watch Calaveras Kate (Rosemary Clooney [George Clooney’s aunt]) belting out a number there…and Scotty making a fool of himself over some hootch and being thrown out a window.

Not convinced? Well, here’s a website with many screen grabs (link) of Red Garters.[36] And check out the clip of the song Brave Man below, the latter part of which features several of the abstracted sets.

The film’s bold look earned its art directors Hal Pereira and Roland Anderson and set decorators Samuel M. Comer and Ray Moyer an Academy Award nomination for Best Art Direction (Color).[37] Given the film’s Oscar™ nod—which other Hollywood art directors would likely be aware of—the likelihood of coincidence seems vanishingly small. Its minimalist design and that it’s applied to a Western town makes it difficult to believe that both “West of Mars” and “Spectre of the Gun” could have coincidentally arrived at the same specific and abstract solution to their Old West sets; a style neither show ever employed for another setting.

There’s a spectre of a smoking gun here. After all: imitation is the sincerest form of Hollywood.

But wait! There’s more!

For one thing, there’s a direct connection between Red Garters and “West of Mars”: they both have the same [credited] writer, Michael Fessier. It’s possible he may have suggested the Red Garters design to the Lost In Space production, but we’ll need to dig to check. In any case, the August 25, 1966 “Shooting Final” script for “Mars” mentions stylization but is vague on specifics:

Smith and Will are walking along the sidewalk of a glorified “SPACE” version of a stylized old western city, stores open at the front, etc.

Interestingly, outdoor daytime scenes in Red Garters are played against vivid yellow skies and earth, not dissimilar to those depicted in the unreleased UPA pilot short Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat from the year prior (1953). Such stylization was definitely in the air in that period.

Michael Sporn’s blog (link) shared this Colliers spread on the unreleased Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat. Cartoon Brew reported on it (link). The lone surviving print (faded) can be viewed here (link).

It’s also been suggested that Red Garters‘ abstracted sets were themselves inspired by photographer John Florea’s Life Magazine spread on the 1948 film Yellow Sky, which posed the cast against bold colored backdrops with things like a teller window floating in the air or a bar floor rail but no bar.[38][39][40] (The photos from this shoot seen here are badly faded and tend towards the magenta, so excuse their poor quality and very rudimentary color correction.)

Minimalist sets were nothing new even then of course. They were a common stage convention and also utilized in film fantasy sequences. The year prior to Red Garters the film The Band Wagon (1953)[41] featured some similarly abstracted settings in its “Girl Hunt ballet” sequence (which in part inspired Michael Jackson’s Smooth Criminal video, even replicating Fred Astaire’s iconic outfit), but note that those are employed in an improbable/impossible stage-bound sequence within the story and not in the film’s broader setting.

Jump to 4:47 for a subway, 6:44 for the suggestion of a skyline and a fire escape on a nonexistent building, and, most notably, 7:30 for the club, the most “Spectre”al set.

No matter how you slice it, “Spectre of the Gun” was employing long-established production design conventions. It didn’t invent them.

But, as oft happens, things perceived as firsts are often riffs on the works of largely-forgotten trailblazers. Star Trek’s popularity ensures its use of the abstract Western sets is remembered whereas its predecessors are not. Innovators yield to popularizers. That it happens is understandable, but it’s not good history, media or otherwise.

And yet…

Whatever its inspiration, we’re not about to dismiss Star Trek’s employing this look, because there remains something notable in its use of such stylization. Its episode manages to pull off something that these example antecedents didn’t: making the design support the story premise. In “Spectre of the Gun” the fragmented setting and “its manifest unreality”[42] reinforces the conceit that this has all been created from Captain Kirk’s shaky conception of what the Old West was like. That unreality becomes especially stark in the nightmarish moments leading to the climax, where illusory objects and characters cast shadows on the all-too-near “mountains” and “sky,” and wherein the arrangement of the marching assassins changes repeatedly with no regard for reality.

Contrast this to “West of Mars” where there’s no reason for the fragmented sets except—apparently—to ape Red Garters. And Red Garters itself looks terrific but it is minimalistic for no reason that relates to the story being told.[43]

So while the abstracted Western look absolutely wasn’t pioneered (pun intended) by Star Trek, the creativity on display there was understanding how to employ that style for both budgetary and storytelling reasons. As we’ve said from the beginning, it’s unnecessary to mythologize Star Trek and give it approbation for work it didn’t do because its own accomplishments are significant enough.

— 30 —

Even the Paramount logo got red skies in Red Garters.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to our pals at Star Trek Lost Scenes for the restored behind the scenes pic from the filming of “Spectre”, and for providing some of the script pages we’ve shared here.

Buy their amazing book here (link).

Revision History

2020-11-21 Original post.

2020-11-23 Section Bones McEarp edited to include a video clip DeForest Kelley in the You Are There episode mentioned, and to add a brief description of the show.

2020-12-22 Section Horseplay Hooey revised slightly and new end note 24 added to address a question pertaining to who actually was cast in the dropped role of the Rider. The section The Axed Ox updated to reflect corrections posted to the Memory Alpha source we cite. Section Welcome to Limbo County amended to clarify that the credited screenwriter of Red Garters is also credited on Lost In Space’s “West of Mars”.

2021-2-09 Added the excerpt from the Lost In Space script “West of Mars”. Moved one paragraph for better narrative flow.

2022-07-17 Added source quoting actor Rex Holman about the firing of the actor originally slated to play Morgan Earp.

2022-08-26 Added image of excerpt from a Fred Freiberger memo concerning stylized sets. 2022-10-25 Section Horseplay Hookey and end note 24 revised slightly to reflect recently uncovered information about the actual identity of the actor cast to play the Rider character.

2022-10-25 Section Horseplay Hooey and end note 24 revised slightly to include newly uncovered information concerning the casting of the “Rider character. Section Exit Earp was edited and end note 26b was added to update to reflect recently uncovered information about the expulsion of an actor.

2022-12-13 Section Welcome to Limbo County amended to include the example of the UPA short Howdy Doody and His Magic Hat.

End Notes

* FACT TREK Comment: So where does Cushman’s account of the horse stunt come from? It’s possible he saw a shooting schedule which set the horse play scenes to be shot on day 6 (although no such thing is in evidence in the Roddenberry or Justman papers at UCLA today), but even if he did, that’s a rookie mistake because you NEVER trust the schedule. Why? The reality is the shooting schedule can and often does change at any point from the time it’s put to paper to the time the scenes are—or are not—shot. If not a schedule, the only other thing we can guess is that it was based either on an anecdote to this effect or because scenes in the 50s range were scheduled for day 6 and Cushman concluded the stunt was shot then. Either would be a mistake.

But the real problem is he didn’t stop there. Not only does Cushman write that the scenes were filmed on day 6, but assumes and reports that Dial was on set without verifying that from the production reports and—worse—invents a narrative about how long the scenes took to shoot. That’s not history. That’s pure fabrication.

Sources

UCLA, The Gene Roddenberry Star Trek Television Series Collection (1966-1969). Specific documents called out below.

Inside Star Trek : The Real Story (Herbert F. Solow and Robert H. Justman, 1996)

Writing

Moonlighting

[1] UCLA, Paramount Collection.

[2] More about this July 11, 1968 letter at Star Trek Fact Check: Gene Roddenberry's Letter to Gene Coon about 'Spectre of the Gun', posted November 6, 2014 (link)

[3] Memo from Gene Roddenberry to Fred Freiberger, May 15, 1968, Subject: Grey Cover Script Blue Pages "The Last Gunfight" (5-14-68) by Lee Cronin, p4. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

Outline Draft or Copy?

[4] These Are the Voyages - TOS: Season Three, Chapter 05: Spectre of the Gun, Marc Cushman with Susan Osborn

[5] Story Outline for “The Last Gunfight” by Lee Cronin, both as submitted and retyped. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[6] The Trouble with Tribbles: The Story Behind Star Trek's Most Popular Episode (David Gerrold, p157, 179, ebook). Original edition The Trouble With Tribbles: The Birth, Sale, and Final Production of One Episode of Star Trek (David Gerrold, First Printing May 1973, p138, 160)

[7] Monday April, 22 1968 cover letter from Fred Freiberger to Stanley Robertson, Subject: “The Last Gunfight.” UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

What’s In a [Script] Name?

[8] Memo from Gene Roddenberry to Shirley Stahnke, March 22, 1968, subject: Lee Cronin - Writer - Star Trek - ST-92. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[9] Memo from Bob Justman to ALL CONCERNED, June 28, 1968, subject: Title Change. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[10] Estimated Finish Cost document, July 13, 1968, “Spectre of the Gun”. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[11] Hour of the Gun (1967) on the Internet Movie Database (link)

Casting

Bones McEarp

[12] May 9, 1968 de Forest Research Report for “The Last Gunfight”. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[13] True West, DeForest Kelley, by Mark Boardman, March 8, 2017. (link)

[14] Hollywood Dreamland, Musings on the Golden Age of Hollywood, Sunday, April 5, 2009, Hour of the Gun (1967) (link)

The Axed Ox

[15] Gregg Palmer on the Memory Alpha Star Trek wiki (link). The article in question has been updated since this post first appeared and now correctly indicates he was cast but never filmed.

[16] Hollywood Reporter, Gregg Palmer, Bad Guy in John Wayne’s 'Big Jake,' Dies at 88, Mike Barnes, November 5, 2015 (link)

[17] Gregg Palmer on the Internet Movie Database. (link) As of Dec. 2020 this entry still lists Palmer appearing in the “Spectre of the Gun:, where he was cast but never filmed.

Fact Trekkers

[18] de Forest Research Report for “The Last Gunfight”, ibid

Chek[h]ov’s Gun[s]

FACT TREK COMMENT: The title of this section is wordplay on the dramatic principle known as Chekhov's gun (Чеховское ружьё) (link) as attributed to playwright Anton Chekhov.

[19] Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal (Stuart N. Lake, 1931, First Edition, Houghton Mifflin), p146

[20] True West, Virgil’s Sixgun: At the Old West’s best-known gunfight, Virgil Earp may have used this state-of-the-art sixgun by Phil Spangenberger, September 6, 2016. (link) “The only firearms that can be identified with any certainty are the two 7½-inch barreled, .44-40 Colt Single Action Army revolvers used by Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury. These Frontier Six-Shooters were retrieved at the site, right after the fight and were recorded.” FACTTREK COMMENT: In the climactic gunfight all the Earps (not Holliday) appear to wield Colt Single Action Army .44-40s. It appears Kirk, Spock, Bones, and Chekov have similar guns. Scotty is carrying something that looks pearl-handled but we couldn’t find a good look at it.

[21] Stagecoach to Tombstone: The Filmgoers' Guide to the Great Westerns, by Howard Hughes, p. 10. Published in 2008 by I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Production

Horseplay Hooey

[22] Cushman, ibid

[23] Memo from Gene Roddenberry to Fred Freiberger, May 16, 1968, Subject: Continuation of Memo "The Last Gunfight" Blue Pages, p1. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[24] FACT TREK Zoom interview with Joseph F. D’Agosta on 9 September 2022. We raised the question regarding the identity of “Richard Anothony” with Joe because the 22 May 1968 revised cast sheet for the episode indicates a “Richard Anthony” whose personal information matched a “Richard Dagosta” (9 February 1946 – 26 November 1970; age 24), and Joe confirmed it was his “kid brother.” Ergo, IMDb’s crediting of the “Richard Anthony” born Ibrahim Richard Btesh (link) is erroneous.

Exit Earp

[25] Daily Production Reports, May 21-24, 27-29, 1968. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[26] Daily Production Reports, May 21-24, 27-29, 1968. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[26a] Actor Rex Holman recalled the firing of Reese—albeit not by name—in the interview, Space Cowboy, By Bill Warren, Starlog #152, March 1990, p. 62 (link)

"I was not originally signed to do that part in the show," Holman admits. "That long ago, it was considered sort of good to be temperamental; Bruce Dern comes to mind. It was looked at as a feather in an actor's cap to be that way. There was an actor on the episode — I don't remember his name — who was signed to do the role. And he got a bit too temperamental apparently, and Vincent McEveety fired him, so I went up a notch."

[26b] FACT TREK Zoom interview with Joseph F. D’Agosta on 9 September 2022.

[27] Cushman, ibid

[28] IMDb page for Gregory Reese (link)

[29] God Wants What Men Want, The Morning Call, Paterson, New Jersey, March 31, 1966, Thursday, p26 (link)

[30] When Did You Last See My Mother, Daily News, New York, New York, January 4, 1967, Wednesday, p270 (link); Antigone, Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, New Jersey, January 14, 1967, Saturday, p9 (link)

[31] Fortune and Men’s Eyes, The Record, Hackensack, New Jersey, January 16, 1967, Monday, p42 (link)

Now Entering Limbo County

[32] Photo. Revisiting the ‘O.K. Corral Fire Aftermath’ by Dr. David D. de Haas (link)

[33] Memo from Gene Roddenberry to Fred Freiberger, May 15, 1968, ibid

[33a] Memo from Fred Freiberger to Gene Roddenberry, May 2, 1968. Shared by the Roddenberry 366 project on Facebook. We cannot find a valid link to the page at this time.

[34] Red Garters (1954) on the Internet Movie Database (link)

[35] Cinéphile caprice. Blog of Fernando Usón Forniés on Cinematographic Analysis. November 12, 2016 “Vanguard in Technicolor: Red Garters (George Marshall [and Richard Mueller], 1954).” in the original Spanish (link) or Google Translated to English (link).

FACT TREK COMMENT: This link is to a thorough analysis of the film’s bold color palette, which the author credits to Technicolor Color Consultant Richard Mueller (link to IMDb). The film’s color styling reminds us of 1990’s Dick Tracy for its bold simplicity. (See also the same blog for “The plane as canvas: Richard Mueller, genius of color, genius of cinema” in the original Spanish (link) or Google Translated to English (link)).

[36] Look at the Gems blog, April 23, 2014, Red Garters (link)

[37] Best Production Design Academy Award on Wikipedia (link)

[38] The Ray & Wyn Ritchie Evans Foundation, Red Garters (link). Note about the film’s look being inspired by the Life Magazine Yellow Sky photos.

[39] Google Arts & Culture. Title: Yellow Sky. Publisher: TimeLife. Photographer: John Florea Credits: Life Magazine. Copyright: © Time Inc.

[40] Angela Rossini on Memory Alpha (link). The article identifies the broadside (poster) seen on the Saloon exterior—depicting the burlesque version of the Mazeppa story (link)—as having been made for the Sophia Loren, Anthony Quinn vehicle Heller In Pink Tights (1960). Click this link to see a few seconds of the relevant sequence in the film’s trailer (link).

FACT TREK COMMENT: The Mazeppa burlesque play is in fact historical, so the inclusion of the barely-seen advertisement is logical, if awfully specific for something pulled out of Kirk’s sketchy conception of the old West. Coincidentally, in Yellow Sky there is a nearly identical depiction of Mazeppa behind the bar in a saloon. That play was gender-swapped from the original story. ‘Mazeppa’ is Lord Byron’s poem based on Ukrainian folklore about young gentleman Ivan Mazepa, whose punishment for an indiscretion is being tied naked to the back of a wild horse. Chekov’s lucky this is not how his illusory death played out.

[41] The Band Wagon (1953) on the Internet Movie Database (link)

[42] Cinéphile caprice. ibid

[43] The 3D Film Archive website (link) lists Red Garters as one of “many titles announced for 3-D production during 1953 that were ultimately filmed flat,” but it is mentioned on other pages of the site and other sources seem to indicate it was shot in 3D. If 3D was planned perhaps the “floating” scenery was designed to exploit the 3D effect. Despite our best efforts, to date we can’t say if there’s any truth to the 3-D claim.

Bang. You’re illogical.